In Memoriam

Credit: Kristin Laidre

PBSG acknowledges the valued contributions made to polar bear research by our previous members.

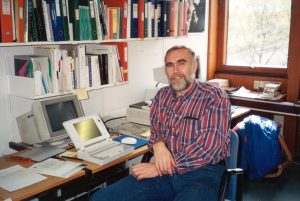

Ian Stirling (1941 – 2024)

Credit: Daniel J. Cox / arcticdocumentary.org

Ian Grote Stirling died on 14 May 2024 in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. As the world’s preeminent polar bear scientist for over 50 years, he published many of the seminal works on polar bears. He was a pioneer in wildlife research and is the most cited author on polar bear ecology, management, and conservation. While best known for his polar bear research, Ian was also deeply involved in the research and conservation of seals and other marine mammals throughout his career.

Born in Nkana, Zambia in 1941, his family moved to Kimberley, British Columbia where Ian’s love of the outdoors, hunting, and fishing drew him into pursuing zoology as a career. Ian completed his B.Sc. at the University of British Columbia and then his M.Sc. there on blue grouse. Moving to Canterbury University, New Zealand, he completed his Ph.D. on Weddell seals in 1969. A post-doc on Australian fur seals at the University of Adelaide, Australia, ended when he joined the Canadian Wildlife Service (now Environment and Climate Change Canada) in 1970 where he worked as a research scientist until he retired in 2007. As an Adjunct Professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Alberta since 1979, Ian co-supervised a coterie of graduate students and was incredibly generous with his contributions to many other aspiring wildlife ecologists.

Ian often said he was a natural historian but his contributions to polar bear management and conservation were profound. He recognized early on that the impacts of climate change were potentially challenging for Arctic ecosystems and polar bears, in particular. Ian was a strong advocate for long-term research, and it was his tenacity to keep his research moving that allowed him to gain concrete insights into how changing sea ice conditions were affecting polar bears. Ian was prolific having authored or co-authored over 300 scientific articles, including over 250 peer-reviewed papers and he never stopped publishing even in “retirement”. He was a strong advocate of science communication and was in great demand for his public talks on polar bears. Ian wrote five books on polar bears, which were incredibly popular and remain the go to source for insights on their natural history, management, and conservation. His book, Polar Bears: The Natural History of a Threatened Species, won the outstanding publication award in wildlife ecology and conservation in the Book Category from The Wildlife Society in 2013.

It is not so much the volume of science that Ian produced but the impact that his science had that is so important. There was no topic too small or too big for Ian. The foundation for Ian’s research was “The Lab” and the people in it. The Lab was the hub around which so many people worked and passed through. Ian was incredibly generous with this time and while not the primary focus of his work, he took on many graduate students and mentored dozens of young scientists from around the world. His influence will continue through the next generations of scientists he has trained and influenced.

To think of Ian as an Arctic and Antarctic scientist ignores many of his many contributions that span the latitudes between. He was actively involved in South American fur seals and sea lions and for years, sat on the Hawaiian Monk Seal Recovery Team. He took great satisfaction in being able to contribute to saving this endangered species. Ian was a member of the Committee of Scientific Advisors to the Marine Mammal Commission which oversees all marine mammals including whales in the United States.

Today, scientists are recognizing the role of Inuit traditional knowledge about Arctic ecosystems. But decades ago, Ian was at the vanguard of collaboration with Inuit. He worked closely with Inuit hunters in the Western Arctic and this bond lasted across generations. In 2000, Ian was made an Officer of the Order of Canada not only for his expertise on polar bears but because he had earned the respect of Inuit through the incorporation of their traditional knowledge into his research. Ian was involved with the Inuvialuit Game Council, Labrador Inuit Association, and Nunavut Wildlife Management Board on polar bear management and research initiatives for many years. In addition, Ian also promoted women in science at a time when wildlife biology was dominated by men. He was ahead of his time in so many areas.

Ian was recognized for his many contributions and received honorary doctorates from the University of Alberta and the University of British Columbia. He was a recipient of the Canadian Northern Science Award, the Norris Award for Lifetime Achievement from the Society for Marine Mammalogy, the Polar Bear Range States Conservation Award, the Queen’s Golden Jubilee Medal, the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee Medal, and the Weston Family Prize for Lifetime Achievement in Northern Research.

Ian was a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada; a scientific advisor to numerous groups including the World Wildlife Fund, Polar Bears International, the U.S. National Academy of Sciences; the first Canadian to be elected President of the Society for Marine Mammalogy; and was a past member of the Canadian Federal-Provincial-Territorial Polar Bear Technical Committee.

For 50 years, Ian was a member (1974-2024) and past chair (1981-1985) of the IUCN/SSC Polar Bear Specialist Group. He was very active in the Group and worked tirelessly to advance the management and conservation of polar bears. The Group met in Seattle shortly after his passing and his presence at the meeting was sorely missed.

Ian is survived by his wife Stella, children Lea, Claire, and Ross along with six grandchildren.

Prepared by PBSG member and former student Andrew E. Derocher, with contributions by PBSG member and former student Nicholas J. Lunn

Markus Dyck (1966 - 2021)

Credit: Jasmine Ware

Markus Guido Dyck, polar bear biologist for the Government of Nunavut (Canada), died on April 25, 2021, at the age of 55 in a helicopter accident, along with a pilot and helicopter engineer. He was surveying polar bears over the frozen sea ice of Lancaster Sound.

Markus stood out in the Canadian North. He had a long distinctive beard, a German accent, and had become a fixture, not a visitor. He stood out among biologists, arriving on the international stage of polar bear research and management through grit, persistence, and talent.

Born in the small town of Riedlingen, Germany, Markus began his life working as a customs agent and later in the German military. In 1990, he was stationed at the German Army Training Establishment at the Canadian Forces Base Shilo in Manitoba. Markus fell in love with the wild of Canada, and on a final leave, he visited Churchill to see polar bears. It proved to be a life-changing experience.

Markus immigrated to Canada and chased the dream to study polar bears. In the 1990s he lived and worked in Churchill and volunteered at the Churchill Northern Studies Centre. He graduated from Brandon University with a bachelor’s degree in Zoology and completed his master’s degree in Natural Resource Management at the University of Manitoba. He spent summers on solitary field studies – observing polar bears catching char in the High Arctic, and observing polar bears observe tourists in Churchill.

Markus and colleague Elizabeth Peacock working on immobilized bears in the Canadian Arctic. Credit: Steve Ambruzs

After his studies, he worked as a technician for the Government of Nunavut with polar bears, for the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, and taught at the Nunavut Arctic College in the Environmental Technology program. During this time, he went on to publish backlogged data – analyzing the bacula of harvested bears to develop evolutionary hypotheses, and investigating those bears killed in defense of life and property to inform local wildlife management. He did not stray from controversy and wrote pieces on whether polar bears could survive a future with reduced sea ice, a few which garnered rebuttals by others, myself included. He was always honest in his views and assessments. This integrity allowed Markus to develop long, trusting relationships with stakeholders across the circumpolar North. Over the years, he developed a keen sense of comradeship with the people of the North. He found kindred friends and dogs and settled into the Arctic for decades.

I met Markus catching polar bears by helicopter in Davis Strait; he continued to work with me as a field technician in Nunavut. He would expertly orchestrate a year’s worth of logistics including caching hundreds of drums of helicopter fuel across the Canadian Arctic; he kept our bear handling equipment, drugs, and safety gear in a condition befitting a German soldier.

When Markus died in the tragic helicopter accident, he was Nunavut’s territorial polar bear biologist, a position which he had held since 2012. I held this position previously and know how well how Markus fit the environment and vice versa. It was in Markus that Nunavut found someone with the necessary unique combination: scientific knowledge, field know-how, and a staunch advocate for both polar bears and the Inuit people. His dedication created a consistency and institutional knowledge that is often lacking in Arctic wildlife management. He was able to represent Nunavut’s interests both with the Inuit Hunters and Trappers and at the international level in research, management, and policy. In this capacity, he published numerous, important assessments of polar bear population size and conservation status. He collaborated with a large array of scientists on studies ranging from food ecology to detection of bears via satellite imagery, from sophisticated genetic and toxicological assessments to changes in denning and habitat use over time.

Above all, Markus was an expert field biologist. He spent springs and summers at the top of the world doing the solitary work studying bear behavior for months at a time, and later sampling bears by helicopter for multitudes of studies and surveying bear populations. He spent winters with his dogs, crunching data, preparing for fieldwork and crisscrossing Nunavut talking with hunters.

Credit: Elizabeth Peacock

When I worked with Markus, we knew that our fieldwork was dangerous, it was at the front of our minds as safety preparations constituted a large part of logistics. Markus was uncompromising when it came to safety. Down days were plentiful, waiting for safer weather, but we felt the work had to be done for the appropriate, science-based management and conservation of polar bears. We spent thousands of hours flying and ski-dooing across the landscape doing the work of polar bear research and management. As all friendships that develop in the field, we spent days in cabins waiting for the weather to clear talking about science and life. Drinking tea, playing cards, watching the fog and wondering if the spot on the side of the far hill would develop into a bear that would later visit the cabin. Markus once volunteered to sleep in a tent rather than our small one room cabin. He would rather face the polar bears outside than listen to the snoring herd made up of biologists, the pilot, engineer and hunters. But someone had forgotten to pack the electric safety fence, so he spent the afternoon stacking empty fuel barrels around his tent as an alert system made to tumble down in a cacophony in case of a marauding bear.

My fondest memory of Markus was on Akpatok Island, lying on our bellies peering over the cliffs down to the shallow turquoise water of Ungava Bay. We were sneaking up to look face to face with the thick billed murres, whose young were taking their first flights down to the mouths of the bears on the beach. We were waiting for the helicopter to return from the Quebec coast. An uneasy feeling, alone on an island full of bears. Waiting, wondering about the helicopter, checking our backs for bears. Markus, smoking (he later quit!) and joking.

Markus will be missed and would likely be surprised by the void he has left. Self-deprecating and humble, I don’t think he realized the impact his short life has had on the people that were lucky enough to befriend him. Nunavut and the Arctic has lost a fierce advocate for polar bears and the North, and a true and talented field biologist.

Prepared by PBSG member Elizabeth Peacock MD Ph.D., with contributions by PBSG-member Martyn Obbard Ph.D. and Jasmine Ware Ph.D.

Gerald Garner (1944 – 1998)

Dr Gerald W. Garner, a member of the IUCN/SSC Polar Bear Specialist Group, passed away on February 15, 1998. He leaves a legacy of outstanding accomplishment, typified by a career dedicated to ecological research. His studies have enhanced the conservation community’s understanding of species and supported enlightened management actions to the betterment of wildlife resources. His contributions and publications extend beyond the subject of polar bears and include white-tailed deer, pronghorn antelope, caribou, wolf, brown bear, musk oxen and Pacific walrus.

Dr Gerald W. Garner, a member of the IUCN/SSC Polar Bear Specialist Group, passed away on February 15, 1998. He leaves a legacy of outstanding accomplishment, typified by a career dedicated to ecological research. His studies have enhanced the conservation community’s understanding of species and supported enlightened management actions to the betterment of wildlife resources. His contributions and publications extend beyond the subject of polar bears and include white-tailed deer, pronghorn antelope, caribou, wolf, brown bear, musk oxen and Pacific walrus.

In 1986, Dr. Garner began research on polar bears in the Chukchi and Bering seas for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Alaska Fish and Wildlife Research Center; now the U.S. Geological Survey/Alaska Biological Science Center. As the Polar Bear Project Leader, he was responsible for conducting population studies that defied meaningful field investigations owing to the vastness of the area and multiple, jurisdictional issues. His leadership and tenacity resulted in the substantial expansion of our scientific knowledge of polar bears in the Chukchi/Bering seas and, later, into other areas of the Russian high Arctic, Severnaya Zemlya Islands, the Laptev and Kara seas, the Novaya Zemlya and Franz Josef Land archipelagos, and the Barents Sea. He was instrumental in testing and developing aerial survey procedures for polar bears, in pioneering satellite telemetry of adult male polar bears, in developing aerial den survey procedures for Wrangel Island, as well as investigations of genetics, stock separation and potential viral sources of disease.

Gerald Garner earned a B.S. in Zoology/Wildlife Management from Oklahoma State University (1967) and an M.S. in Game Management from Louisiana State University (1969). Upon graduation, he worked as a wildlife biologist for Pennzoil Corporation, a game biologist for the Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation and as a wildlife consultant. He returned to academia in 1973, earning a Ph.D. in Wildlife Ecology from Oklahoma State University in 1976. Following two years as an Assistant Professor at Sul Ross State University, Texas, he joined the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Washington, D.C. in 1978. He transferred to the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in Fairbanks, Alaska, as a Supervisory Wildlife Biologist, in 1980. His work developing baseline biological data on the wildlife resources of the refuge earned him the Secretary of Interior’s Commendation Award. In 1986, he accepted the position of Polar Bear Project Leader (Western Alaska) for the Alaska Fish and Wildlife Research Center.

Gerald will be remembered for his commitment to seeking knowledge of the ecology of polar bears and other wildlife; for his staunch support of scientific inquiry; for his work ethic, devotion and dedication to research and conservation; and for an unwavering commitment to achieving these goals. His list of publications serves as a legacy to these accomplishments yet, by themselves, do not do justice to his contribution to science. His accomplishments will continue to serve as an example for peers, and for those who follow in his footsteps.

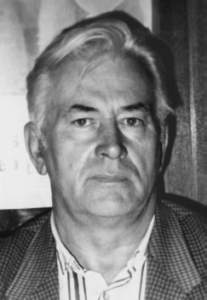

Nils Are Øritsland (1939 – 2006)

Professor Dr Philos Nils Are Øritsland, a gifted scientist who contributed much original thought and research to polar bears, died unexpectedly on November 24, 2006 after a short illness. He participated actively in several meetings of the IUCN/SSC Polar Bear Specialist Group and continued collaborative studies with several members on a variety of research projects on polar bears right up to his untimely death. With his passing, the IUCN/SSC Polar Bear Specialist Group lost a highly valued colleague and friend, as have the polar bears as well.

Throughout his early education and his later career, Nils Are was dedicated to Arctic research and in particular to studies of the energy balance of free-living animals, particularly polar bears and seals. As a young scientist, in 1968-69, along with another well-known Norwegian polar bear biologist, Thor Larsen, he spent a whole winter on an island in the remote archipelago of Halvmåneøya in Svalbard in the Norwegian Arctic in order to study polar bears. While there, he conducted a series of physiological experiments on heat balance in live bears, especially cubs, the results of which are still fundamental to all subsequent studies of heat balance in polar bears. Later, in 1971-1974, he performed a series of ingenious and original physiological experiments on heat balance in polar bears in Churchill, Canada. Included in his research during this period were some ground-breaking experiments on the effects of oil on polar bears. Although there was some controversy about the experiments at the time, over 30 years later his research on that topic remains the complete basis of our understanding of this significant environmental threat to wild polar bears.

Through most of his professional career, Nils Are was dedicated to Arctic research and continued to pursue his career through both the University of Oslo and the Norwegian Polar Institute, focusing on the energetics of Arctic mammals. From 1974-84 he was the scientific leader of a multidisciplinary research program on reindeer under the UNESCO program “Man and Biosphere”. The aim of the program was to understand the biological basis for the existence of the Svalbard reindeer. At the same time, he developed the Bioenergetics Group at the Zoophysiological Institute, University of Oslo, which continued to focus on all aspects of energy balance in mammals.

Nils Are received his Dr. Philos. degree in 1978 for a thesis entitled, “Some applications of thermal values of fur samples in expressions for in vivo heat balance”. In 1986 he was honored by the “Nansen reward” from the University of Oslo for outstanding research in the Arctic. In the period 1987–1992 he was Professor in Zoophysiology at the same place.

Nils Øritsland at the Norwegian Polar Institute

Nils Are was director of the Norwegian Polar Institute from 1991 to 1993. He resigned when the Norwegian Parliament decided to move the institute from Oslo to Tromsø in 1993, though he continued to work there until the move was completed in 1999. Through the last years before he died, he consulted privately on the development of population models for the management of wildlife. Simultaneously, he continued to work closely with several of the members of the IUCN PBSG on the development of a comprehensive population and energetics model for polar bears, a work which, sadly, was never completed.

Nils Are was an unusually gifted scientist and a truly original thinker. He was also a totally honest man who remained unafraid to speak his mind, clearly and without rancor. One could not find a finer person to call a friend and colleague. He leaves behind a wonderful and close family as well as many scientific colleagues who continue to miss his insights, sense of humor, and simple good companionship very much. At the same time, we remain grateful for all that he did for us individually and for his field of science and, of course, for his long-term research that taught us so much about polar bears.

Prepared by PBSG members Ian Stirling and Øystein Wiig

Malcolm Ramsay (1949 – 2000)

Dr Malcolm Alexander Ramsay, a member of the IUCN/SSC Polar Bear Specialist Group, was killed in a helicopter accident in the Canadian High Arctic on May 21, 2000 while returning to the field research station at Resolute, Nunavut at the end of a day of studying polar bears and seals.

Malcolm was a long-standing member of the Polar Bear Specialist Group. His PhD was with Dr Ian Stirling on the reproductive physiology and ecology of polar bears, and was completed in 1986. Malcolm was a full professor at the University of Saskatchewan and supervised a number of graduate studies. He and his students have contributed greatly to the body of knowledge on polar bear anaesthesiology, contaminants, hibernation, fasting, lactation, energetics, body composition, evolution and ecology. Malcolm also contributed research on ungulates, carnivores, other marine mammals, avian ecology, sharks, coral reefs, natural history, evolution, life history strategies and undoubtedly more. Malcolm’s curiosity was matched only by his energy and enthusiasm for new ideas. He had 50+ publications, an active graduate and personal research program, and was a popular teacher at his University.

Malcolm’s work was some of the most innovative and exciting research ever conducted on polar bears. Malcolm’s colleagues and friends spanned scientific disciplines and were literally distributed across the world. He was a wealth of information on new techniques, new technologies, and was completely generous with his contacts, ideas, and suggestions. He did not seem to care about the usual politics or propriety issues associated with high profile research projects. He was as generous with his equipment and time as he was with his ideas and support. We all benefitted from Malcolm’s work and, because of Malcolm’s openness, his ideas and initiatives were not lost with him. Others are already taking much of his research forward, which is certainly what Malcolm would have wanted.

Although new faces and new ideas are already emerging, all will miss Malcolm’s insight and critical mind. He has left us a shared memory that is all the more precious because it is ephemeral. Those of us present today will remember Malcolm as a friend even more than we will miss him as a colleague. This dedication acknowledges Malcolm as a valued colleague and honors him for his professional achievements. But for many (perhaps all) of us, it is much more. Most of us have shared the time of our lives, bad weather, small cabins, accepted the same risks and enjoyed the same wonders as Malcolm. We will miss his laughter, irreverent sense of humor, cheerfulness, generosity, energy, council, open spirit, goodness and friendship. The memory of Malcolm is something we share as a group and will carry forever. He was his own man, a good friend, and we mark his passing with respect and sorrow.

Savva Uspenski (1920 – 1996)

Professor Savva M. Uspenski, the well-known Russian biologist and one of the original members of the IUCN/SSC Polar Bear Specialist Group, passed away on April 17, 1996. Professor Uspenski conducted much of the original research on polar bears in Russia. His first expedition, in 1964, was dedicated to the study of female polar bears in their maternity dens on Wrangel Island. Through his initiative, a research station of the All-Union Research Institute for Nature Protection and Nature Reserves (since 1991, re-named the All-Russian Research Institute for Nature Protection) was established on Wrangel Island in 1969 for the purpose of studying polar bears. Investigations of the ecology and behaviour of polar bears in maternity dens during winter were carried out at this station and in other areas of the island by Professor Uspenski and his colleagues A. Kistchinski and S.E. Belikov until 1979, and later by other biologists from the State Nature Reserve.

During 1980–90, studies of the ecology of polar bears also included Herald Island and the northern coast of the Chukotka peninsula, a primary objective of which was to count the maternity dens in each area. Later, these investigations were carried out in other parts of the Russian Arctic as well. Although Professor Uspenski did not take part in the field work of these later expeditions, his support and advice were important to the success of the scientific programs.

Professor Uspenski was born December 9, 1920 in the town of Zvenigorod, near Moscow. After studying at the Moscow Fur-Down Institute in 1937, he tied his future to the Arctic. Besides conducting research on polar bears, he studied birds, was instrumental in the development of the natural protected areas network in the Russian Arctic, and was one of those responsible for introducing muskox in Russia. In 1963, he defended his Doctor of Philosophy in Zoology on avifauna of high latitudes. He remained a member of the Polar Bear Specialist Group until after the 10th Working Meeting of the Group, which was held for the first time in Russia, in autumn 1988.

Professor Uspenski published over 200 scientific papers, brochures and books. His books include The Birds of the Soviet Arctic, Polar Bear, and scientific popular books such as The Home of the Polar Bear, Living on the Ice, and others. Some of his books have been translated into German and English. He was a long-standing editor of the magazine Game and active in scientific matters up to the time of his death. The memory of Professor Uspenski and his contributions to arctic biology will be remembered by his many colleagues and friends.